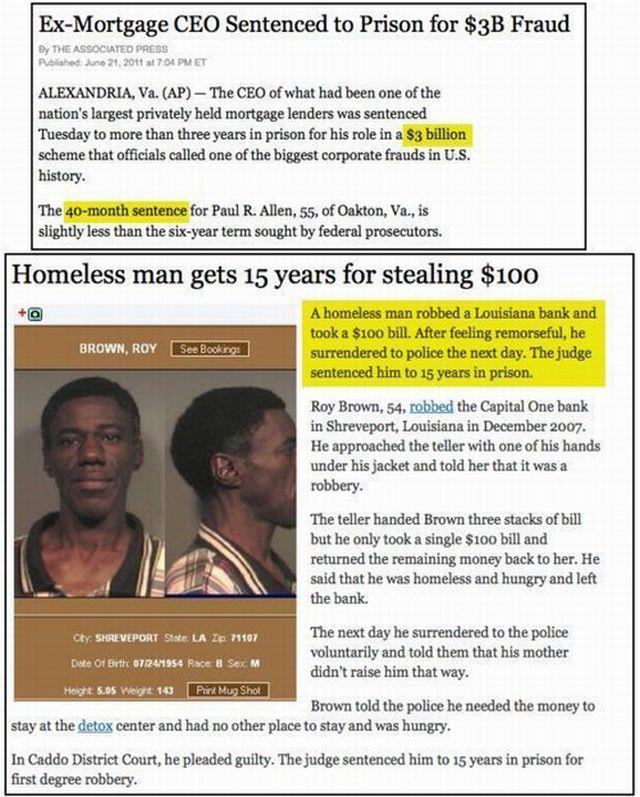

With headlines ripped straight out of a Charles Dickens novel, finding out that a homeless man gets 15 years for stealing $100 while another man (richer, of course) gets only a 40-month slap-on-the-wrist sentence for committing one of the US’s largest corporate fraud cases by stealing $3 billion only affirms why movements such as Occupy Wall Street are cropping up all throughout this country and others as well—because people are exhausted by the disparity in how the rich are treated. Whatever illusion to fairness that our judicial system, or system in general, propagates is exposed in this glaring juxtaposition of sentences. Where the homeless man’s trial, incarceration, and sentencing probably cost several times more than what he stole, the rich man not only gets a lighter sentence but is implicitly applauded for his audacity in stealing billions. Which confirms the age-old caveat of American politics and economy: Just steal more.

This is no longer a question of liberal or conservative, Democrat and Republican, since such binary opposition has led us astray as a clever distraction imposed by a clever hegemony devoted to swiping every last penny from this country without reciprocal punishment when caught. Charles Dickens exposed much of this class disparity to a 19th-century audience. And though primarily directed towards a British audience, Dickens was able to affect changes due to his stark depictions of the elite and the poor all throughout the world. Now we’ve denigrated ourselves, and society at large, to no longer taking heed of the words of men and women much more prophetic and didactic than us, and have thus reverted back to this antiquated belief that the rich are just better, as if they don’t die and thereby must be elevated on a societal pedestal and worshiped. All of which contradicts and violates a very carefully mapped out social contract that our Founding Fathers created over two hundred years ago.

A much more modern reincarnation of Dickens could arguably be seen in some of the works of Michael Moore, in which he satirically exposes class disparity and champions the “little man.” Despite what you think of Moore, he did an excellent job in his 1989 documentary Roger & Me in depicting the vast liberties we afford those with economic power, such as the then CEO of General Motors, Roger Smith. Not to overly summarize or simplify the plot of the film for those who have seen it, Roger & Me shows Roger Smith’s effect on Flint, Michigan, Moore’s hometown, in which Smith closed down several GM plants over the course of several years in the 1980s, laying off more than 35,000 people, while moving plants over to Mexico and giving himself raises on a quarterly basis. In the short-term, Smith did arguably save GM millions of dollars by contracting cheap labor in different countries. But because he was only thinking of the short term benefits, Smith was unable, like so many other CEOs, to foresee the deleterious effects it would inevitably have on the future of the company twenty some odd years later.

The headline above and Roger & Me and Dickens forewarn of a society that treats people differently in an ascending hierarchy as eventually failing because a society based on principles of greed and wanton excesses cannot sustain due to a lack of a big picture. The private sector has bought out our government with money steeped in the blood of the people’s labor, clapping each others’ backs after robbing us blind. We no longer have a system prepared to deal with this lack of representation of the people, and thus now we see both the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street—both different in their own respects—garnish popularity due to the increasing amount of distrust of our political system.

The headline above and Roger & Me and Dickens forewarn of a society that treats people differently in an ascending hierarchy as eventually failing because a society based on principles of greed and wanton excesses cannot sustain due to a lack of a big picture. The private sector has bought out our government with money steeped in the blood of the people’s labor, clapping each others’ backs after robbing us blind. We no longer have a system prepared to deal with this lack of representation of the people, and thus now we see both the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street—both different in their own respects—garnish popularity due to the increasing amount of distrust of our political system.

The failure of our system that has allowed the rich free passes in many ways started with the massive overhaul of regulation back in the ’80s by President Reagan, which of course led to the Roger-Smiths of the world to do as they did—i.e. shut down manufacturing in the States and replace our labor with other countries’ labor so that they could cut more corners for short-term profits and returns while bankrupting multiple communities at the same time. But the most horrific political move that is mostly to blame for much of our economic troubles now is the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act back in 1999, a piece of legislation responsible for much of the growth and sustainability of our country since the Great Depression since it separated the interests of commercial banking and investment banking. With its repeal, banks could then control much of the capital circulating, amassing a staggering amount of the wealth, and then bankrupting the rest of society.

Though if it were as simple as reinstating Glass-Steagall, then Obama’s 2010 enactment of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act would have been sufficient to regulate capital’s flow so that it balances out—though some have commented on the lack of the Dodd-Frank Act in protecting the rights of consumers that was seen in Glass-Steagall. Many of the problems come from this idea that the rich gained their position and that, as Herman Cain put it, “those who are poor just need to work harder” — one of the dumbest things repeated way before Dickens. There is not a single person within this country (or any country for that matter) that cannot find one single person that helped them get to their position, and not even the mythos of Herman Cain can support a system that looks like Milton Friedman having sex with Objectivism. No one is just born into their status. We live in a society based on social contracts, both implicit and explicit, that dictate how we treat one another. And perhaps it is time that we move towards a paradigm in history that, like Dickens did, defines a healthy relationship between private interests and the people’s interest so that we don’t get disparities as drastic as the one above.

Just Steal More,