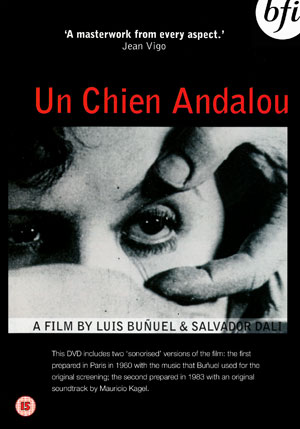

Un Chien Andalou (which translates An Andalusian Dog) was directed Luis Bunuel and written by both Bunuel and Salvador Dali. If you’re unfamiliar with Bunuel’s work, then you should at least be familiar with Dali’s iconic surrealist work, which comes across in the 1929 silent surrealistic work of Un Chien Andalou. It’s a fifteen minute film that is perhaps one of the most intriguingly complex works ever composed in the cinematic medium.

And both Bunuel and Dali have admitted that there is no strict logical interpretation that can be derived from the film’s imagery, which goes in between cutting a woman’s eye open to watching as ants crawl out of a hole in a man’s hand to a blind, androgynous woman poke a severed hand in the middle of a crowded intersection. It’s just a weird fifteen minutes that explores the nature of dream logic and the suppression of human emotions after traumatic events.

While no one will watch Un Chien Andalou and absolutely understand what Bunuel and Dali were trying to get at, it is perhaps one of the most important cinematic pieces of all time due to the revolutionary techniques in telling a story. For one, it rejects conventional conceptions of how a film’s plot is conceived. As a surrealist composition of random images juxtaposed one after the other with no logical interpolation and the background music of Richard Wagner’s opera “Tristan und Isolde” (which is an old Germanic myth), Un Chien Andalou will make you both wonder what the hell just happened and engage you in the conversation of the mind.

It was never meant to be a popular film. In fact, Bunuel and Dali prepared the night of the premiere by filling their pockets with rocks in expectation the audience would respond not only negatively but violently, but were instead met with applause and critical acclaim—which might seem odd for a 21st-century audience pumped with CGI and sensible and logical plot streams that are commercially profitable. But initially Un Chien Andalou enjoyed a bit of popularity for its bold expression that is even today unmatched. It is also interesting to note that with this film, Dali was effectively accepted into the artistic community of the surrealist which then led to his later more iconic work. So really, Un Chien Andalou not only serves the annals of cinematic history but also artistic history, as well.

But even if you are still skeptical, remember that it’s only fifteen minutes, less than a standard running time for a sitcom. And while that’s not great reason to see a film, Un Chien Andalou is just not one of those films that you can genuinely portray to a modern audience that isn’t familiar with cinematic theory, art theory, or even the history of the two because it has no conventional markers of what most people consider a film. So, enter at your own precaution, for it is sure to boggle you all the way through.

Un Chien Andalou,