The idea of ingesting a drug to combat addiction to another substance may seem strange to some, to others, heretical. There is however an ever growing body of research to back up the use of certain drugs for combating addiction, and the most promising of these are the psychedelics. These substances are well suited to this task, in that they are of very low toxicity and safe when administered in a therapeutic context, and they are not addictive. If over used they have a tendency to induce bad trips which act as a buffer discouraging further heavy use. Addiction tends to center on the denial or burial of past material, whereas psychedelics tend to bring life issues to the surface where it is hard to hide from them. They can also work in a multifaceted fashion on addiction, as shall be discussed. Addiction is incredibly costly to society as a whole, with the National Institute on Drug Abuse stating it costs the US over $500 billion a year, with tobacco and alcohol being some of the leading causes of mortality the world over, and we currently lack any really effective treatments for either dependency. Thus it would be most unwise to pass up any potential avenues that may aid in combating addiction.

The idea of ingesting a drug to combat addiction to another substance may seem strange to some, to others, heretical. There is however an ever growing body of research to back up the use of certain drugs for combating addiction, and the most promising of these are the psychedelics. These substances are well suited to this task, in that they are of very low toxicity and safe when administered in a therapeutic context, and they are not addictive. If over used they have a tendency to induce bad trips which act as a buffer discouraging further heavy use. Addiction tends to center on the denial or burial of past material, whereas psychedelics tend to bring life issues to the surface where it is hard to hide from them. They can also work in a multifaceted fashion on addiction, as shall be discussed. Addiction is incredibly costly to society as a whole, with the National Institute on Drug Abuse stating it costs the US over $500 billion a year, with tobacco and alcohol being some of the leading causes of mortality the world over, and we currently lack any really effective treatments for either dependency. Thus it would be most unwise to pass up any potential avenues that may aid in combating addiction.

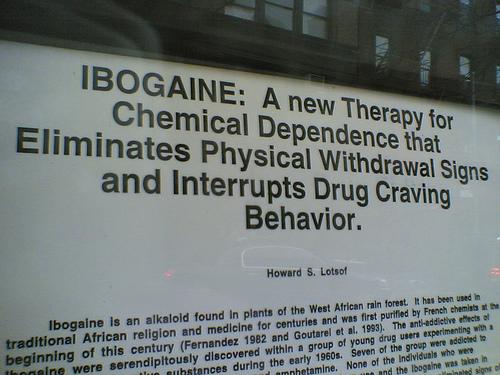

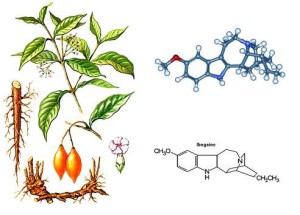

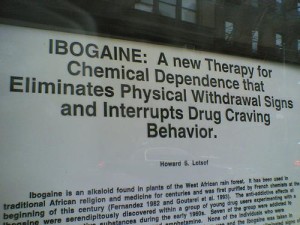

Ibogaine has generated particular interest for its anti-addiction properties. It is an alkaloid isolated from the root bark of Tabernanthe iboga which has a long history of use for healing and spiritual purposes in central Africa. A key part of its use in a traditional context is the death and rebirth experience of an initiatory flood dose, allowing the user to return to a new beginning. The addiction interrupting properties of ibogaine were discovered accidently by Howard Lotsof in 1962, who was addicted to heroin at the time. He was gifted some ibogaine by a chemist friend and when consumed he had an exhausting 32 hour trip. Going to bed likely swearing off ibogaine, he woke up the next morning surprised to find he had no desire to use heroin. This was unexpected and made a great impact on Lotsof, and although not a doctor or a scientist he campaigned hard for research to be conducted on its anti-addiction effect, and he played a key role in generating initial scientific and medical interest and research into the compound. Methadone is a standard treatment for heroin addiction, but this acts as a substitution, and is a highly addictive opiate itself, so one is simply swapping an illegal addiction for a pharmaceutical one. Ibogaine has a much deeper and broader effect on addiction.

Ibogaine appears to work on addiction in a number of interesting ways. The ibogaine molecule interacts with many different receptors in the brain, but has a low affinity for them. This is one of the reasons that the medical establishment is not attracted to conducting research on it; it is deemed to be a “dirty” drug, medical science preferring drugs that are more direct and specific in action. Ibogaine acts in a multifaceted way, even on a biochemical level. It works in part by resetting receptors in the brain to a pre-addiction state. It can alleviate the withdrawals from drugs such as opiates, which is a big help in breaking the addiction cycle. It also induces a waking dream state, a highly personable experience taking place behind closed eyelids, where one will likely encounter repressed memories and examine past and current life issues, but in an emotionally detached manner. This period of reflection aids in a detached introspective examination of the roots of one’s addiction and the behavior patterns associated with it. Ibogaine is converted to noribogaine by the liver and has prolonged effects, often experienced as an afterglow and mood lift post session, and this compound is thought to play a role in the anti-addictive effects of ibogaine.

Ibogaine also causes a long term increase in the expression of a growth factor protein known as glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF). GDNF is a highly neuroprotective protein, promoting the survival and differentiation of dopaminergic and motor neurons, and has the ability to induce neuronal sprouting in the brain. GDNF also appears to play a major role in ibogaine’s longer term anti-addiction effect. Ibogaine increases GDNF via an autoregulatory positive feedback loop. So the increase in GDNF caused by ibogaine induces neurons to produce mRNA, which acts as biochemical blueprint in the manufacture of further GDNF. Other life style factors, such as exercise and sunlight, also increase expression of this protein. Ibogaine is highly lipophilic, and can remain in body tissues for months, so extending this anti-addiction effect. People have found booster doses following a flood session helpful in keeping on this path, and others have had success through microdosing, as the effects of ibogaine and its sister alkaloids in iboga are cumulative and build up in one’s system over time. So for some this may be a beneficial and safe approach to using this plant in a way that can be integrated into day to day life and without the ordeal of a flood dose experience.

Ibogaine, the classic ‘anti-drug drug’ is not a panacea for treating addiction. It can however provide a window through which people that have the will can enact change. If seeking ibogaine in this context, the person seeking treatment will require support post session and changes in life style should be made prior, such as avoiding situations or people that may have associations of past drug use. Ibogaine requires work and will on behalf of the person using it to maximize chances of success. MAPS is conducting ongoing research at ibogaine clinics in New Zealand and Mexico looking at ibogaine’s long term effects on addiction.

Ibogaine, the classic ‘anti-drug drug’ is not a panacea for treating addiction. It can however provide a window through which people that have the will can enact change. If seeking ibogaine in this context, the person seeking treatment will require support post session and changes in life style should be made prior, such as avoiding situations or people that may have associations of past drug use. Ibogaine requires work and will on behalf of the person using it to maximize chances of success. MAPS is conducting ongoing research at ibogaine clinics in New Zealand and Mexico looking at ibogaine’s long term effects on addiction.

A structured and supportive setting plays a key role in addiction treatment, and this can take a number of different forms. In the Native American Church, peyote is viewed as a powerful treatment for alcoholism. Members of the Church believe peyote will show them the truth about their lives and give them insight and guidance, and past studies have found positive effects of peyote on social, mental and physical well-being. Suggestibility may also be playing a role in this setting. Alcoholism is a major affliction among the Native American population, around four times higher than the US average.

In the UK alone, alcoholism costs the NHS £3 billion a year, and this figure is rising, with alcohol misuse being one of the highest risk factors for ill-health in the EU. In the past LSD has been used successfully to treat alcoholism, at a range of dosages, although alcoholics who experienced a transcendent state during their session were far more likely to demonstrate a long term improvement in their conditions, and such states were induced more commonly with higher doses. A review of old studies conducted in the 1960’s and 1970’s found that 59% of people reported lower levels of alcohol misuse following treatment, compared to 38% who received the placebo, which is as good as any current alcoholism treatments. Patients who experienced a profound sense of cosmic unity or ego death seemed to change their outlook on their addictions. Alcoholics Anonymous co-founder Bill Wilson claimed his experience with LSD played an integral part in his recovery from alcoholism, and encouraged him to found AA. He didn’t view LSD as a magic bullet for alcoholism, more of an ally that could set up a goal and incentive for recovery. A study published this year looking at many thousands of people found no association between psychedelics and mental health issues. In fact there were less mental health issues in the psychedelic using group, and lifetime LSD use was correlated with less psychiatric hospital visits and a lower use of prescription drugs.

Recent studies have used psilocybin in the treatment of alcoholism and tobacco addiction. These are ongoing pilot studies with a small sample size so far but the results are encouraging and further research is certainly warranted. Of the four people who have been treated for tobacco addiction with psilocybin, one year after treatment three were no longer smoking and one had gone from a pack a day to one cigarette a week. Despite the small number of people in this study so far, this is encouraging, as the average success rate of quitting smoking is between 20 – 40%.

Psychedelics act in a number of different ways in the brain that impact addiction. They act on the receptors in the brain associated with drug seeking behaviour, while reducing blood flow to areas of the brain associated with emotional processing and higher function that tend to be overactive in depressives. This restrains the negative circular thought patterns associated with addiction. The temporary chaotic state induced by psychedelics seems to weaken reinforced brain connections and dynamics and the experience provides a window of reflection where people can view their life and addiction issues from a wider perspective. People who were more successful in quitting smoking had higher ‘mystical experience’ scores, and in other studies, the psilocybin induced mystical experience was found to cause positive changes in measures of life satisfaction and well being, as well as long term personality change, particularly in openness. This compromises personality traits such as placing value in aesthetics, emotion, openness to new experiences and a curiosity to further knowledge. It seems that this experience and the change in values and outlook also plays a key role in the anti-addiction effects of psychedelics such as psilocybin.

An increasing number of therapists are using ayahuasca in the treatment of substance addiction, and there is a growing research interest in this area. There are numerous positive subjective reports from people who have self medicated with ayahuasca to treat addiction, and participants in studies have reported positive lasting psychological and behavioral changes. Addiction expert Dr Gabor Maté views ayahuasca working on addiction in multiple ways; by allowing users to see the baggage associated with their addiction and appreciate it does not have to be a part of them, and by allowing them a positive experience of love for the self. Recent neuroimaging research on ayahuasca have found evidence of changes in brain structure in long term users, associated with positive changes in behaviour and feelings of life satisfaction, so changes in neuroplasticity within the brain may play a role in its anti-addictive effect. Ayahuasca also causes a serotonin up regulation which may have anti-depressant qualities, assisting with enacting life change post session. Past studies looking at members of the União de Vegetal (UDV) Church revealed they felt ayahuasca had a profound impact on their lives. Many reported they were better able to see destructive behavior patterns, and there was a tendency to discontinue alcohol, tobacco, cocaine and other drug addictions. It is also interesting to note that an appreciable proportion of long term ayahuasca users had suffered from alcoholism and depression prior to joining the UDV. In British Colombia ayahuasca has been used with success in addiction treatment among indigenous people there by Dr Gabor Maté, and in Peru it has been used to successfully treat cocaine addiction, notably in a therapeutic community setting at the Takiwasi Center, with future addiction research planned there.

Cannabis may play a role in the treatment of addictions. Both THC and cannabidiol (CBD) have been found to act as neuroprotective antioxidants against the effects of excessive alcohol use and neuro-degeneration of the white matter of the brain. Cannabis has been suggested as a much safer substitution treatment for alcoholism, cocaine and opiate addiction. Recent research has found CBD to markedly reduce cigarette consumption in smokers, and it may reduce cravings with other substances.

Cannabis may play a role in the treatment of addictions. Both THC and cannabidiol (CBD) have been found to act as neuroprotective antioxidants against the effects of excessive alcohol use and neuro-degeneration of the white matter of the brain. Cannabis has been suggested as a much safer substitution treatment for alcoholism, cocaine and opiate addiction. Recent research has found CBD to markedly reduce cigarette consumption in smokers, and it may reduce cravings with other substances.

Unfortunately, at present, all classical psychedelics are considered Class A or Schedule 1 substances, deemed to have a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use. However various psychedelic agents have been used by different cultures in different parts of the world to successfully treat addiction and other afflictions, and there is an ever expanding body of evidence to suggest their efficacy. Draconian laws and numerous regulatory and financial hurdles currently stand in the way of any researchers hoping to work with these substances. This could be preventing the treatment of a condition that exerts a vast cost on many human lives, and on society as a whole.

Trip to Sobriety: Psychedelics and Addiction,