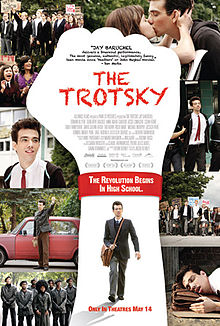

Imagine what it would look like if Leon Trotsky was reincarnated into a seventeen-year-old Canadian high school student who tries to unionize the students of his public high school, and that’s what ‘The Trotsky’ was all about. Leon Bronstein (played by Jay Baruchel) is a disenfranchised teenager with radical ideas of revolution and unionization, in which his seriousness is borderline hilarity. Bronstein is completely committed to living out the life of a contemporary Trotsky; from his estrangement from his father, to exile, revolution, marriage, and even his death, Bronstein, a confused teenager who’s not quite sure of who he is, adopts Trotsky’s personality and life as a means to deal with society and growing up—and all the struggles that entails.

Leon Trotsky is often the unsung hero of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 Russia. The essential right-hand man to Lenin, Trotsky was known for his disciplinary ‘permanent revolution’, which inevitably led him into trouble when Stalin took charge. A proponent of the people, Trotsky was fervently opposed, as an intellectual and idealist, to any and all forms of fascism and unwarranted control by either the government or corporations. And perhaps he makes the perfect metaphor for what it’s like to grow up in today’s modern high school, with often borderline-fascist control that essentially creates the disillusionment and disenfranchisement of a student of the twenty-first century. But there’s one problem that Bronstein faced as the reawakened Trotsky figure—a problem that Trotsky often cited in his autobiography: apathy.

The film, layered in Communist and Soviet innuendo and overtones, often asked the question both to the audience and the actors: Is it boredom or apathy? Boredom, quite frankly, is a state of drowsiness that an individual can be roused from, and thus can be fixed. Apathy, on the other hand, is an indifference to any and all events occurring around an individual—what Karl Marx would probably diagnose as a lumpenproletariat, or a person who is completely disconnected with class consciousness and thus severed from action and revolution. And it’s certainly a valid question to ask, not only to the students of this century, Generation Z, but to society at large. Are we merely bored or apathetic? Because it is the latter, then all hope for the state of things changing is lost.

But, the film asks, if it is merely boredom that rules over our lives, then who should it and will it be that will lead the revolution to rouse us from our lethargy? A man like Trotsky? Someone so disconnected and a virtual anachronism and unpleasantly unwavering in his convictions that revolution, to him, is not a question of if but when? It’s certainly an interesting and essential question to ask. But even if you don’t subscribe to a Communistic vision of how the world should be run (and even if you don’t know what exactly Communism entails—like most Americans), the film can still be enjoyed for its witty and cynically optimistic—if that makes sense—outlook on the state of being. With superb performances, ‘The Trotsky’ is one of the best films to come out of Canada in the past ten years, and will certainly be enjoyed for generations to come as a poignant statement of this generation.

The Trotsky,

Smike

8 May 2011Are you familiar with Guy Debord? I wrote an article on his ideas being given a shot of new life by Banksy, not too long ago. It sounds like you’d be interested in his writings.