By: Gahdly Popawitchen

This is a bit of a throwback in terms of film reviews. Many have been raving about the recent film The Social Network. And while I’m not disputing its already-proven critical acclaim, I will go out on a limb and state that Jesse Eisenberg has done better, five years before The Social Network, actually. The film that I speak of is, The Squid and the Whale; and while the movie is no longer out in theaters, it can easily be rented, bought, stolen, or any combination thereof. And if you’re still skeptical about watching it, read the review below.

The Squid and the Whale is not only the product of its creator, Noah Baumbach, but also of its culture, commenting on the social trends in divorce and the use of therapeutic undertones. With that said, the film does well in documenting such trends in a unique, imaginative way that could never be reproduced. And while other films have depicted the effects of divorce, none have done so extraordinarily as Baumbach’s. The dialogue evokes both the comedy and tragedy of the Berkman family, while the depth of each character is dissected masterfully—exposing their hardships, embarrassments, and shortcomings.

The film starts with a relatively happy-go-lucky family in 1986 Parks Slope, Brooklyn, where the contentions and animosities between Bernard and Joan Berkman (both writers) unravel behind closed doors. While it wasn’t entirely shocking when the parents called the dreaded “family conference” to announce their impending divorce to their children (predicated on Bernard’s intense chauvinistic, nigh-Hemingway-like contempt for his wife’s literary success, and his own literary and physical impotence), it was nonetheless heartbreaking to witness the proceeding mental disintegration of their sons, Walt and Frank, as they tried to cope with the schism in their family. To further traumatize their sons, Bernard and Joan’s intense narcissism leads to the joint-custody decision that inevitably—and unsurprisingly—caused conflict. Even the cat wasn’t spared in the puerile divorce squabbles.

Not soon after, each son picks a side. Frank, a naturally, good-hearted mamma’s boy, chooses Joan’s side. Walt, idolizing the accomplishments of his father, chooses Bernard’s. Each parent’s shortcomings then gets projected and amplified through the sons. But rather than a display of self-indulgence, the son’s mimicking of their parents becomes a cry for help.

Walt gets a girlfriend, Sophie Greenberg—supposedly his first—and doing as his father said that he could do better, demeans her incessantly until he loses her and realizes how much he liked her. He then develops a crush on Lili, one of his father’s students who moved in with them (and whom Bernard happened to be sleeping with, as well), in which the irony is not lost on Joan when she states, “So, they like the same women now, too.” But the ultimate pantomiming of Bernard’s characteristics comes when Walt takes Pink Floyd’s,’Hey You’, calls it his own, and plays it at the school talent show thereby winning $100. Such an act of plagiarism and mimicking reflects Bernard’s tawdry, kitsch, and—to use his word—philistine disdain for originality.

On the other side of the coin, Frank’s story develops even more tragically. Scarred by the divorce, the 12-year-old develops a sailor’s mouth, drinking habit, and a disturbing penchant for masturbation all going unnoticed by his parents, brother, and other authority figures. It eventually leads to the climactic scene where Frank is forgotten and neglected (primarily by Bernard), and thus gets black-out drunk and pukes up the worm of a tequila bottle with no supervision whatsoever. The neglect of his father is paralleled to the neglect of Joan by Bernard, in which both cases Frank and Joan express their contempt through sex—one masturbation, the other infidelity.

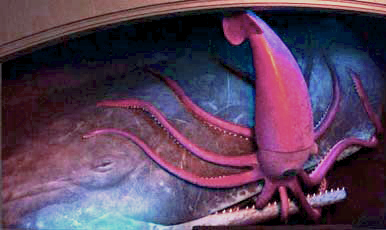

The nexus seems to indict Bernard’s extreme pretentiousness, inveighing attitude, and falsely pedantic sense of literature. And while Joan is not guiltless in her escapades, she’s nonetheless reacting to the brutish personality of her ex-husband. They all are. When Bernard collapses in front of the house from what’s later diagnosed as exhaustion, there’s little sympathy to be found for him. Not even Walt, the son that sided with him to begin with, can find it in himself to stay with Bernard in the hospital, but rather chooses to revisit the American Museum of Natural History (a blast from his past) to see the squid and whale exhibit—which he described to his psychologist earlier in the film when asked about his fondest childhood memory. That sense of childlike awe and mysticism is then not only elicited from Walt revisiting and pondering over the exhibition but also from the audience.

The film very much ends in question; or at least, there’s more questions unanswered than there were at the beginning. But that’s the point. The film points out the absurdity and uncertainty of real life. It then brings us back to the reality of the situation through its personalization of divorce, best exemplified in Walt and Joan’s back-and-forth: “JOAN: Don’t most of your friends already have divorced parents? WALT: Yeah, but I don’t.” No longer a question of statistics, divorce becomes in The Squid and the Whale a matter of individual experience that has lasting effects on each character.

So by no means go and see this movie expecting a happy-ever-after ending. The movie purposefully attempts to be uncategorized, and that’s why it should be celebrated—for its raw, heart-wrenching depiction of divorce, spectacular acting, and unrivaled originality.

The Squid and the Whale,