Shared by Tom Hastings @ Hasting on Nonviolence

Back in 1977 The New York Times began taking polls of how Americans feel about Congress. Not until this week, with the clearly craven Congressional inability to stand up for the rights and aspirations of average Americans, has the disapproval rating sunk to a startling low of 82 percent.

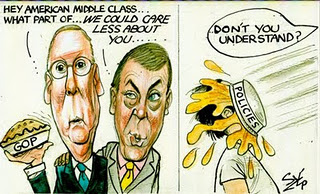

This record low is a reflection of the realization that in the crunch the Republicans will defend the privileges of the rich, let the middle class slide into poverty, and cut off social services to the poor–and that the Democrats will fail to stop them.

More than any debate or vote in memory, these basic betrayal characteristics were revealed to us all during this long and bitter haggle, really more fractious, arguably, than any debate in US history since the literally pugnacious antebellum bitter battles adumbrated the Civil War.

Applying the conflict forensics peculiar to my field of Conflict Resolution–normally reserved for attempting to predict outbreaks of physical hostilities in divided societies from Africa or the Balkans or Central Asia, an enterprise under development since its proposal in 1957 in the Journal of Conflict Resolution–we can offer some tentative warnings about America in 2011 and beyond, and I include these two for the moment.

If more jobs aren’t created, Americans will rebel. In the end, we don’t care if they are high paying, in the public or private sector, or particularly fulfilling. We want to care for our families and we want to do that by working and producing. We are not as worried about our particular job security as much as the overall robust security of the availability of jobs.

There is no particular guarantee about how this rebellion will manifest, but even the very union of the country is not assured in the end. The debt debate was only a snapshot of a national set of divisions that go far deeper than loyalty to a nation-state, but go to essential identity values that eclipse everything.

Historically, we have many examples of population shifts responding to or presaging the dissolution and recreation of national boundaries. The greatest such wave was the 1947 migration of Hindus into what was becoming India and Muslims out of that nascent state into East and West Pakistan. Other migrations have responded to other factors, but national politics ranks as high as famine and economic pressures–and they are often connected, of course.

On an anecdotal level, I’ve been interested in the last decade in this phenomenon in the town where I live, Portland, Oregon, as young people stream here from red states or red counties in Oregon, toward what is more and more a place of experimental evolutionary attempts to break out of our national obsessions with military might and consumerism, toward some sort of inclusive authenticity and forward movement with a long view of sustainable society. I know amazing people, now Portlanders, who come from Headstomp, Kentucky

or Luvgun, Texas, to help create a softer future, one of dialog and diversity, solar powered even in our rainy town.

While most Americans aren’t too excited about a woo-woo culture, they reject the nearly Talibanic aspects of the Tea Party, as shown by the new outright disapproval of the influence of that movement on the debt debate. That influence shoved aside the obvious answers:

– closing tax loopholes that allow rich people and their corporations to avoid taxes

– cutting the grotesquely bloated Pentagon budget long before cutting social services or education.

So we shall see where this leads. Gorbachev and Yeltsin didn’t plan to break up the USSR. Nehru didn’t intend to divide India. Milosevic certainly didn’t mean to push Yugoslavia into separate states and John C. Calhoun never said he’d like a secessionist South or a civil war. Sometimes history overtakes and overpowers toward a new day, for better or worse. Will there be a USA with the same boundaries in 50 years? In 15? It’s hard to say. Studies have shown that expressions of deep grievance have an average of a bit more than 13 years before fully maturing into hot conflict. What will historians say about the Dysfunctional Debtonator Debate of 2011? Will it be a recognized harbinger of a descent into destruction or will it mark a low point before some national healing and new unity? The choice is no one’s but ours.

About Tom Hastings – I am an old peace and justice activist from the 60s who just never stopped. At some point, when I was a community organizer working for Waging Peace in northern Wisconsin, I realized I needed a lot more education and theory to become a better activist. I picked up a few degrees and now I teach it. I’ve written a few books and spent time in many jails and three prisons for my nonviolent actions and see no reason to stop in our era of cascading problems from the war system.

The End Of The U.S.A.,