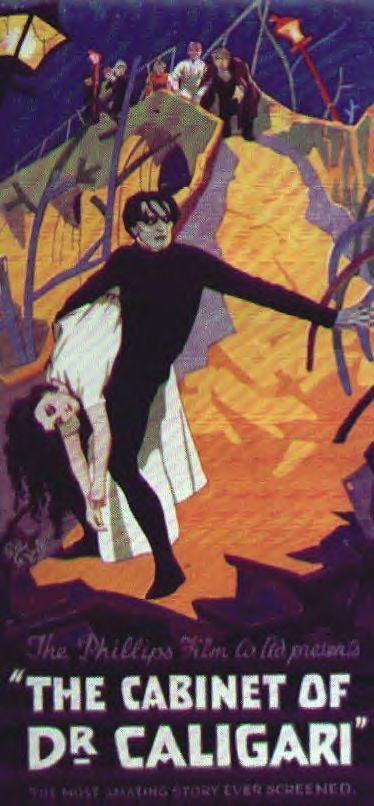

When I was first told that I just had to watch a silent film, that it would be for my benefit, I probably had the same reaction that most would have for the past fifty years: Why can’t I just watch a film where the actors talk? And then to find that it was made by a bunch of German Expressionists, which is apparent in the set design, about a metaphor for the after effects of World War I. When do the history lessons and sanctimony ever end? But to finally find out that it is the film most cited for inspiring the film noir genre just made me writhe in agony after agreeing I’d see the film.

And now that I’ve seen it, you may be wondering what are my impressions? Not bad. If anything, the film still rivals a lot of films made within the past ten years. It has depth, meaning, good special effects (for its time period—which was 1920), and great acting. The cherry on top was that it ended with a twist ending, one of the first of its kind, and better than Christopher Nolan’s or M. Night Shyamalan’s twists. In more ways than one, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was a revolutionary film.

At the time of its release, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari would have been instantly recognized as an anti-war film—expressing the despair of Germans in being led by blind ideology (nationalism) to destroy itself. But if you didn’t know that going into the film, then it probably wouldn’t have been that obvious. It might actually have reminded you of Scorsese’s Shutter Island, with a similar psychological edge and dark, brooding tone. For those of you who don’t want any spoilers then stop reading now and go watch the movie. It’s definitely worth it.

It starts off with a young man, Francis (the main character) talking to an older gentlemen in the woods which is used a framing device to tell the rest of the story. Francis starts narrating how he lived in a small German mountain village that was virtually untainted until one fateful summer when the town hosted a carnival—which is an allegory for social chaos—and a man going by the assumed name Dr. Caligari arrives with a somnambulist—sleepwalker—named Cesare who’s a 23 and never been awake and is under the control of Dr. Caligari. Very early on, Dr. Caligari and his somnambulist, Cesare, catch the attention of gawkers at the carnival which at the same time a string of random, unexplainable murders crop up. Thus, the connection of entertainment and death is made that was so familiar in Post-WWI society—and probably still is. Not soon after the murders occur, Francis’ best friend falls victim which heightens Francis’ resolve to find out who’s behind these killings. This compels him to bring along his betrothed, Jane, on the investigation for his friend’s murder which results in Cesare kidnapping Jane and leading to mob of townsfolk chasing him all across town and then some until he dies of exhaustion in a field and they rescue Jane.

Needless to say, Francis pursues Dr. Caligairi into an asylum only to find out that the evil doctor is actually the director of the institution who specializes in the study of somnambulism. When we’re finally led to believe that Dr. Caligari’s obsession with somnambulism has somehow demented his rationality and morality and led him to kill innocent villagers by directing Cesare as his weapon, we come to discover that this was all a delusion of Francis, and that he and every other villager are patients in the asylum. Dr. Caligari, as it happens, is the actual director of the asylum; but he’s definitely not the evil doctor we were led to believe. Rather, he’s attempting to cure Francis of what modern society would probably call post-traumatic stress disorder.

Francis was obviously a German soldier in the Great War, but it becomes very apparent that he either did not know why or what he was fighting for, or he regretted having to kill so many people, or possibly see so many people die around him—like his best friend. Jane becomes the object of reminiscing on the past, in which her presence is merely a constant reminder of how Francis can never truly reconcile what he saw in the trenches with the illusion of the homefront. And of course, Cesare is the symbolized projection of his youth in this blind, sleep-like haze, not able to fully comprehend what his actions are, or their repercussions, while Dr. Caligari becomes the representation of these leaders and nations using scientific and idiopathic reasons to forge war with the world. The most discernable message then becomes that their true enemy, these soldiers (since Francis was merely an embodiment), was themselves, since the embodiment of all soldiers ended up in an asylum fighting off their own delusions.

What makes the film eerie is at the end when Dr. Caligari says—in a silent fashion—that he now knows how to cure Francis without giving a specific answer which becomes ominous when the Great War’s spirit for blood and national pride continued—though resting for twenty years—into WWII.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,