After the not guilty verdict of Casey Anthony, America responded in the only way it knew how: changing its Facebook and Twitter statuses to PO’d and drumming up some ridiculous federal law that would further curtail civil liberties. Many expressed how we should change the Fifth Amendment’s rule on double jeopardy so that we could gather up a lynch mob and try Anthony as many times as we can. And others, like populist activist Michelle Crowder, proposed a law eponymously called Caylee’s Law so that parents everywhere would feel the sting of ‘justice’ if their child went missing and they, in either grief or ignorance, did not report it.

The law, if passed, would mean that any parent that does not report their child missing within 24 hours or the death of their child within one hour then they would be charged with a felony. Logistically, the law makes absolutely no sense. But already around 700,000 people have signed Michelle Crowder’s petition to pass the law. The only reason Caylee’s Law is gaining any sort of popularity is due to this national sense that we as a nation have to find someone responsible for Caylee Anthony’s murder, and because her mother was legally acquitted we need another head to put on the chopping block. But was it because Casey Anthony didn’t report her daughter missing that caused the death of her daughter? Perhaps it indicates her guilt, but it certainly didn’t cause Caylee’s death. And would this law mean that parents would think twice before murdering their children? No. If anything, it would mean that parents would be even more alert, paranoid and afraid that their child is somewhere in a ditch with a bullet between their eyes after ten minutes of not seeing them—not out of genuine concern for the child’s safety, but because they don’t want to be put in jail.

Caylee’s Law also seems to indicate that highly publicized criminal cases are the norm within society. Didn’t anyone learn from the O.J. Simpson case? Most people charged with murder aren’t loaded with millions of dollars and an A-Team of lawyers there to bust them out of any trouble. Just like most mothers aren’t extremely sketchy and lie to the police after their child has been murdered. But because so much attention is given to these cases, we’re led to believe that they’re a common occurrence. People really need to stop listening to Nancy Grace for ethical legal commentary. The reality, though, seems to indicate the world works a lot differently than what many pundits and news commentators paint it as. Rather than gathering all our information about the justice system from Law and Order—in that the bad guy always, or more than likely, gets what they deserve—we should assume that the justice system works entirely different, in which every defendant that enters that court room is presumed innocent until proven otherwise.

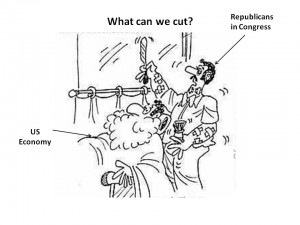

The problem wasn’t any sort of law, or lack thereof, but the fact that the state of Florida, i.e. their prosecutor, could not prove beyond reasonable doubt that Casey Anthony was guilty of her daughter’s death. Just because the media has been covering the case as if she was guilty and treating the case like it was open-and-close doesn’t actually mean that it was. Obviously the results of the case prove axiomatic of just such a fact. But the right response isn’t to get all pissy and flex your populist muscles and yell at politicians—people who aren’t necessarily responsible when it comes to standing up to crowds (i.e. mobs) of people with pitch forks in their eyes—to pass a ridiculous law that makes absolutely no sense in the grand scheme of the justice system and society. What we should be doing is mourning the death of an innocent child, somberly realizing that the justice system is not and cannot ever be the perfect Law-and-Order system that catches the bad guy every forty-five minutes, and that highly-publicized cases are not the norm.

As William Blackstone once commented, “It is better that ten guilty escape than one innocent suffer.”

Caylee's Law: The Flaws of Mob Justice,