If you’re young—say, under 45—chances are you’ve already lost interest in this piece. What does it have to do with you, sitting in the middle of your prime, with the prospect of many more years to make the most of your life on this planet? I can hear some—not all—of you saying: “Some of my best friends are old people.” “Old people are okay, in their place.” “What does ageism have to do with me?” And even if you deny having any such response, it’s my guess that somewhere in your subconscious a voice is saying, “I’m glad I’m not old; old people are so yesterday.”

I speak with authority on this subject, being old myself. I can hear some—not all—of you now: “You’re not old!” “Sixty-one: That’s young!” “You’re a spring chicken!” And when friends and family tell me that, I always thank them and say something like, “I feel great. I feel young. I don’t feel old.” I’m not dissembling; I’m blessed with good health and the genes for longevity, so my odds of living to be old and ripe are pretty good (and I sure don’t mean to goose the gods). I also realize it’s all relative, and that I’m just a kid, according to my 91-year-old mother. But I’ve lived long enough to feel the sting of ageism, and that makes me an authority.

And that is precisely my point. All this talk about how age is just a number resonates. Old people can do anything young people can do (with some biological exceptions). We hear stories often about old people running in the New York Marathon, climbing Mount Everest, sailing around the world, building a house, finally finishing college, earning their PhD, publishing their first book, running for office, and so on and so on. And the collective response to these accomplishments is a unanimous, “Wow, that’s amazing, for someone her age. How much we respect her!”

But words, and media hype, are cheap, and the shameful reality is that every day we also hear stories about old people who are let go from jobs, rejected by employers, denied benefits, abandoned by their families, abused in nursing homes. We hear about their having to choose between food and medicine, about their dying alone and in poverty, and about an epidemic of depression.

In spite of many studies showing that older workers are more dependable than their younger counterparts, and in spite of the fact that older workers are often much more qualified for jobs—given their age, experience, and wisdom—employers routinely reject applications from seniors in favor of the young. Indeed, instead of respecting the applications from people with long and noted careers, employers often toss them into the reject pile without so much as a note of thanks.

Sociologists say old people need more respect in order to remain healthy as they age, and it’s well documented that being able to contribute to society is key to self-esteem. Yet old people (women more often than men—the subject for another rant) are routinely denied this opportunity.

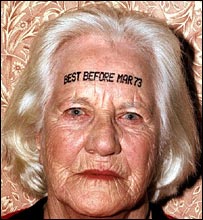

Does my use of the term “old people”—rather than “seniors” or “elders” (more politically correct terms)—rankle you? I hope so. But why should the term “old people” not be politically correct, in fact, a compliment? Old people have survived the slings and arrows of life for decades. They’ve overcome hurdles and heartbreak. They’ve faced and conquered challenges. They’ve been ill and recovered. They’ve raised children and are raising grandchildren. They’ve won and lost. In a word, they’ve earned their wrinkles—and their label.

I’ve often quoted whoever the wise person was who coined the expression, “prayer wrapped in bigotry is still bigotry” (how I wish I’d coined it myself). Well, ageism wrapped in political correctness is no less offensive or damaging. Ageism is insidious and everywhere. It hides behind the impatient rolled eyes of a kid who must wait at the checkout counter behind an old person. It lurks in the laughter at an old person’s forgetfulness. It smolders in young people’s distaste for old people’s choice of music, wardrobe, books, friends, and pastimes.

By rights, old people should be treated with deference and honor. Even countries long known for revering the elderly (China, Russia, and India) are gradually turning away from this tradition. Capitalism is geared toward the powerful, and the power rests with the young. We are obsessed with youth, to the detriment of the aged. Examples of this are too numerous to name, so I’ll mention just one: Hollywood. The youth-centric movie business puts its most talented and experienced actors out to pasture long before they should; good leading roles for actors over fifty—again, especially women—are as scarce as hen’s teeth. “Ageism has become a dirty word in entertainment in recent years because it seems today’s big stars are teens and young adults like Miley Cyrus, 17, Zac Efron, 22, and the Twilight actors. Brad Pitt, 46, and Tom Cruise, 47, are just old men.”

We worship our children, sometimes beyond all reason. Of course, children depend on us for their care and feeding, and are our future, but we sometimes adore them to the point of egregious spoiling. I recently saw an illustration of a kid throwing a wild tantrum, with this caption: “We talk so much about leaving a better planet to our kids, that we forget about leaving better kids to this planet.” Indeed.

By contrast, we marginalize our aging population, those who have paid their dues and set the stage for the rest of us. But here’s the good news. Like any other inculcated attitude or behavior, ageism can be corrected. With raised awareness, a concerted effort, and the desire to change hearts and minds, ageism can become a thing of the past. Unfortunately, this is not likely to occur in my lifetime, as I am already old. But maybe some young people out there will actually read this whole essay, and be the change they want to see. After all, the youth are our future.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Learn more about Rachel’s new novel here —-> Driving in the Rain

Join Rachel on Facebook here —-> The Equality Mantra

Ageism: The Undying Prejudice,